Get out of here bear!

Dawn was already breaking about 3:30 am, when I was jolted awake by a blasting airhorn and Troy Finney yelling “Get out of here bear!” Since the electric fence had died, Troy was concerned about our safety, and slept fitfully that night. As he lay in bed, he heard some splashes, which he thought were salmon. They continued, and they were getting closer! Troy unzipped his tent, and immediately spotted a very large grizzly bear heading straight towards camp! Troy squeezed a few quick air horn blasts and gave a shout, and the bear turned and ran. Who knows what that grizzly would have done if it crossed the river, but we were glad Troy heard it. Was it just curious and about to turn around anyways? Or was God answering our prayers of safety, wakening Troy at just the right time? Either way, God chose to protect us, but I do know that our side of the river was a bad spot for bears to fish from, which pretty much convinced me it was coming to check us out!

So now what were we going to do? We had travelled about 50 feet into our 40-mile trek down American Creek, and already we were having grizzly problems! We had no idea what to expect downstream, but we were pretty sure there would be more salmon, and therefore more bears. Earlier that year, Troy had an extensive conversation with a Katmai Park Ranger, who said in no uncertain terms, “you will have an encounter with a bear on your trip”.

I don’t know if anything could have prepared me for that first trip down American Creek, but looking back, I should have known more about grizzlies before I went. Some men will find every excuse possible NOT to do something, while others will throw caution to the wind and take huge and unnecessary risks. By definition, an adventure requires some degree of danger and unknown risks, so I did not think our trip had suddenly become a death wish. As a lifelong fishermen, I had learned that in order to catch fish, I needed to “think like a fish”, understanding their behavior, life history, food preferences and feeding patterns. I needed to apply the same principle of understanding God’s creation to learn to think like a bear. In Chapter 1, I talked briefly about bears and the history between bears and men. Now, I will dive deeper into the mind of a bear, and hopefully by the end of the chapter you too will be able to think like a grizzly!

Identifying a grizzly.

Two bear species you may encounter in areas frequented by grizzlies include the black and polar bear. Grizzlies, on rare occasion, mate with polar bears, and DNA tests have confirmed hybrid “pizzly” bears shot by hunters. Hybrid black/grizzly bears have never been documented. Hybridization is a key indicator that researchers known as baraminologists use to speculate about created kinds (a.k.a baramins). If two species hybridize, it is possible they descended from an original created kind.

For most people, the two bears they may see occupying the same habitat are the grizzly and black. There are four key features for distinguishing between them, including body shape, facial profile, color, and tracks.

A distinguishing feature on a grizzly’s body is the hump between its shoulders. This is most prominent when the bear’s head is down. Unfortunately, depending on how it is standing, a black bear can also have a hump-like feature over its shoulders, while the occasional grizzly has a very small hump.

Notice the black bear has a very small shoulder hump. Copyright 2000, David E. Shormann.

Notice the larger shoulder hump on this female black bear. Copyright 2000, David E. Shormann

The shoulder hump and brown color reveals the species of bear on the California State Flag. Photo from Wikipedia.

Facial profiles are usually a better way to distinguish between blacks and grizzlies. The grizzly is often described as having a “dished” facial profile, although I have never quite seen how its face looks like a dish. “Concave” may be a better way to describe each side. To understand their facial profile, imagine you had a pet grizzly, and you were petting its face. Starting at the snout, your hands move back and underneath the eye. Your hand would follow a concave pattern, moving out and away from the neck, whereas repeating the procedure on a black bear, the path would be smoother, and maybe even slightly convex, directing your hand toward the neck. And, the black bear tends to have a shorter, more rounded muzzle. Male bears of both species usually have a larger, more robust head than females.

Notice the more concave facial profile of the grizzly bear. Copyright 2007 David E. Shormann.

Notice the more convex-shaped face. Copyright 2000, David E. Shormann

Color is usually the most distinguishing feature between the two. You can probably guess what color most black bears are, although you might be surprised that their color can vary from blue-gray “glacier bears” of Glacier National Park, to cinnamon. Most often though, they are black. Grizzly bears encompass various shades of tan, blond, gold, gray, silver and brown. In Grizzly Almanac, Robert Busch describes a 1971 study by Greer and Craighead where 50% of Montana grizzlies sported a grizzled color pattern, 30 percent were dark brown, and 20 percent were light brown.

These two grizzlies are actually more brown than others. Copyright 2007, David E. Shormann.

A grizzly is almost always larger than a black bear in not only body and head size, but also in the size of its feet and the length of its claws. Grizzlies walk on the soles of their feet, in a plantigrade fashion, where the heel touches the ground. An adult grizzly’s claws can be almost 4 inches long, compared to about 2 inches on a black bear. Claw marks may show in their tracks, with the grizzly’s claw marks extending much farther out in front of its finger or toe pad marks. If you see a track, and it is as big or bigger than a men’s size 10 shoe, then it is most likely the track of an adult grizzly!

Look at the claws on that grizzly! Copyright 2007, David E. Shormann.

Grizzly names

One way to better understand grizzlies is to look at the common names people give them. For example, one of the favorite foods of Katmai grizzlies is Oncorhyncus nerka, more commonly referred to as sockeye salmon. Two other common names for sockeyes are red salmon, describing their spawning colors, and bluebacks, for the blue coloration of sockeyes still at sea, or for those just entering freshwater.

Compare then the rather simple common names for sockeye with those of the grizzly bear, Ursus arctos. Today, reference books tell us that the name “grizzly” comes from the bear’s hair coloration. For example, Audobon’s Field Guide to North American Mammals describes their coloration as “yellowish-brown to dark brown, often with white-tipped hairs, giving grizzled appearance”. More often than not though, grizzly bears do not have this so-called “grizzled” look. Could it be then, that its real name has been lost through time? After all, there is another word that sounds like “grizzly”. In Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, published in 1885, America’s 26th President, Theodore Roosevelt, describes the bear’s name as follows:

“By the way, the name of this bear has reference to its character and not to its color, and should, I suppose, be properly spelt grisly-in the sense of horrible, exactly as we speak of a “grisly spectre”- and not grizzly, but perhaps the latter way of spelling it is too well established to be now changed.”

Perhaps, but did you know that the scientific name for one of the two currently recognized North American subspecies is Ursus arctos horribilis, which means “horrible northern bear!” And those aren’t the only names. In both Hunting Trips and The Wilderness Hunter, published by Roosevelt in 1893, he titled the chapters on grizzlies “Old Ephraim”, a common nickname of the grizzly at the time that referred to a tribe of Israel that had “provoked God to anger most bitterly” (Hosea 12:14). Undoubtedly, the grizzly bear’s actions had provoked more than a few settlers of the American West to anger. While used as a general name to describe bears, there was one bear that earned the title of going down in history as “the” Old Ephraim. In The Grizzly Almanac, Robert H. Busch describes the bear as a famed cattle killer that was chased for 12 years until range conservationist Frank Clark trapped and shot the bear in 1923. Old Ephraim weighed 1,100 pounds and stood 9 ft, 11 inches tall (3.02 meters).

And what about the Native North Americans and the Spaniards? The Koyukon Indians of Alaska called it bik’ints’itldaadla, meaning “keep out of its way”. El Casador, Spanish for “The Hunter”, was the name given to a bear renowned for killing cattle and sheep in California in the 1800s.

And these are just a few of the many names given to grizzlies over the years. While most of these names strike fear in our hearts and remind us that this is an animal we should approach with great caution, other names are less impressive. Lewis and Clark usually described the bears as “white bears” or “yellow bears”, and Roosevelt also referred to them as “Moccasin Joe”, a term referring to their massive footprint resembling a man wearing moccasins. With so many names given to this bear throughout history, we would be wise to consider the reasons, realizing that the variety of names relates to the variety of physical, and behavioral traits of this bear. When we hear the word “grizzly bear”, we should think not only of its color, but also of its potential for harm.

Taxonomy and distribution

The grizzly bear has also been a bear of many names in the scientific community. Biologist C. Hart Merriam listed 86 separate species and subspecies in his 1918 publication, Review of Grizzlies and Big Brown Bears of North America. This was a radical departure from Ursus arctos (“northern bear”), the name given in 1758 to all grizzly bears the world over by Carolus Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy. In the seven-tiered classification system he developed, grizzlies are placed in Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Chordata, Class Mammalia, Order Carnivora, Family Ursidae, and Genus Ursus. A pious Christian man, one of Linnaeus’ main goals in systematizing the tremendous variety of living creatures was an attempt to delineate the original “kinds” described in Genesis. Today, baraminologists speculate that the “created kinds” are probably represented at the “family” level of Linnaeus’ system.

Linnaeus, like most scientists of his day, trusted God’s word. Charles Darwin, on the other hand, set out to disprove special creation by God, and in 1859 published On the Origin of Species. Many scientists bought into Darwin’s false theory on origins, and in 1918, “Darwinism” was all the rage. But the theory was not based on anything scientific, and scientists did all sorts of unscientific things in an attempt to prove that animals were evolving and new species were being formed by the truckload every day. Instead of basing the discovery of new species on thousands of observations, scientists were instead making hasty generalizations. For example, the Smithsonian classified a new subspecies, Ursus horraeus texensis, from the skull of a single bear killed in Texas in 1900. Many other new “species” were also classified from single skulls.

Fortunately, as scientists learn more about the fallacy of evolution and the truth that there are limits to genetic change, the “diversity” of wildlife decreases. Now there are only two subspecies recognized in North America, Ursus arctos middendorfi (Northern Middendorf bear), which is the brown or Kodiak bear of Alaska’s Kodiak islands, and Ursus arctos horribilis, the name given to all other bears in North America. Ursus arctos is the Genus-species name for all brown and grizzly bears worldwide. In other parts of the world, they are usually referred to as brown bears rather than grizzlies, although bears in Eastern Russia and in particular the Kamchatka Peninsula may sport the lighter color patterns common to North American grizzlies. And all bears worldwide are legendary for displaying their “grisly” demeanor at times.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, at one time the lower 48 states probably had well over 50,000 grizzlies, but their population shrunk to under 1000. Today though, their numbers are on the rise in the lower 48, particularly in and around Yellowstone National Park. According to Wikipedia, there are about 31,000 (some estimates put the number closer to 40,000) grizzlies in Alaska, 22,000 in Canada, and 1,300 in the lower 48 states, with virtually all of those bears confined to Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. In Eurasia, there are around 120,000 brown bears in Russia, and most of those are in the eastern half. About 30,000 live west of the Ural Mountains, and about half of these live in Russia’s upper northwest corner. Kazakhstan has about 1,800 bears, and smaller, mostly isolated pockets of bears exist in China, Turkey, Northern India, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. In Europe, about 1200 bears live in Scandinavia, which includes Finland, Norway and Sweden. About 6,000 are believed to exist in southwestern Russia/Romania. Many other isolated pockets of brown bears live in Western Europe, including Italy, Greece, France, Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Habitat requirements

Current estimates place the worldwide total of grizzly bears at about 200,000 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_Bear). Keep in mind though that doing a bear census is just a little more difficult than doing something like counting the number of people in your church, and the actual number may be significantly higher or lower than this. Also, a lot of the data on bear populations is over 10 years old now. Regardless, that is still a lot of grizzly bears!

The habitat and range of grizzly bears is highly variable, but is always dependent upon food availability and population density. And while grizzly bears do not mark off specific territories to possess, they usually have an area of land that they call home and rarely venture from. For example, on the Kodiak Islands, where salmon provide abundant food for bears, their home range may be less than 3 square miles (8 km2). Here, bear densities are some of the highest on earth, at a little under 1 bear per square mile (2.6 km2). In less productive regions like interior Alaska and Montana, home ranges may be greater than 500 square miles. Males tend to have larger home ranges than females.

Good grizzly habitat includes a place with abundant food. Up to 50 bears at a time may be feeding during the peak of the salmon run at Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park. Copyright 2007, David E. Shormann

The large home ranges and amount of space between bears is one reason bears are symbols of wild and untamed lands. With the exception of Kodiak Island and some other coastal grizzly populations, bear densities are usually upwards of 1 bear per 10 to 50 square miles. (26 to 130 km2). In mostly unpopulated Alaska, current estimates place bear populations between 30,000 and 40,000. With an area of 656,425 square miles (1.7 million km2), the average Alaskan grizzly density equals one bear per 16 square miles (42.5 km2). Since not all of Alaska is utilized by grizzlies, it would not be unreasonable to use this data to assume a bear density of 1 bear per 10 square miles. Comparing that to the total worldwide bear population yields a figure of 2.0 million square miles (4.7 million km2) of wilderness required to sustain the worldwide bear population. This is an area roughly half the size of the United States, which seems large, until you consider that Alaska, America’s largest state, with more wilderness than any other, would account for over one-third of the world’s bear habitat. Russia can easily make up the remaining two-thirds. According to the CIA World Factbook, permafrost over much of Siberia is a major impediment to development in this region, as are volcanoes and earthquakes on the Kamchatka Peninsula. These remote places are also prime bear habitat, and will probably remain so for years to come.

A grizzly’s habitat preferences about as diverse as its appetite. When not hibernating, or taking a siesta in a cozy day bed, grizzlies are searching for food. Riparian zones, a term referring to the land surrounding a river, lake, or other water body, are popular choices, especially if the waters teem with salmon, or for Yellowstone’s grizzlies, cutthroat trout. Floodplains are also popular, as these areas provide a water source for bears and their prey, and also contain the preferred marsh habitat of one of their favorite prey items, moose calves. Since these areas are also more frequently disturbed by floods, they often contain higher abundances of opportunistic plants like sedges, a grass that grizzlies like to eat. Many types of berries that grizzlies eat also colonize frequently disturbed areas. One such area is an avalanche chute, which is a narrow lane on mountain slopes where avalanche or rock slides have cut a path through the forest. A study in Montana showed that grizzlies preferred avalanche chutes to other habitat types because of the preferred plant items that were available, as well as the greater abundance of carrion from avalanche-induced mortality.

While bears are truly symbolic of wild places, as their numbers increase, their habitat preferences and search for food bring them into more frequent contact with humans. In Anchorage, Alaska, radiocollared grizzlies were tracked throughout the city, and were found to travel through the cover of riparian zones (forested areas) that wound through the heart of the city. Of the 11 bears studied in the three-year (2005-2007) survey, several descended from the mountains to feed on salmon in Campbell Creek, a tributary running through the heart of Anchorage. For more information on the study, visit the Anchorage Daily News’ website at www.adn.com/photos/wildlife/bears/story/454024.html.

Grizzly bears will occupy a variety of habitats in a single season, seeking to optimize their chances to satisfy their omnivorous appetites. In Grizzly Heart, Charlie Russell described how the bears around his cabin at Kambalnoye Lake on the Kamchatka Peninsula would exit their dens and head for the coast where spring began first. Later in the summer, when the sockeye and char would return, so would the bears. In the Wilderness Hunter, Theodore Roosevelt describes them as bears that “inhabit indifferently lowland and mountain; the deep woods, and the barren plains where the only cover is the stunted growth fringing the streams.”

Although not necessarily territorial, bears are definitely creatures of habit, and will return to preferred feeding areas year after year. This is evident at popular bear viewing areas such as Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park, and the McNeil River Game Sanctuary. I also witnessed this on American Creek. In 2006, I photographed a beautiful mother grizzly with her three newborn cubs on the lower river. In 2007, I was able to photograph the same bear again, resting in almost the same exact spot. I have some favorite fishing spots of my own along the Texas coast, and there is one in particular near Port Aransas that I return to each April, because, like this mother grizzly, I have learned that the fish will be there at a certain time of year.

Besides eating, a bear’s second-favorite activity is probably sleeping, and this also effects its habitat preferences. Bears in more remote places tend to sleep at night and eat during the day, pausing for mid-afternoon naps in their feeding areas by making a “daybed”, which is usually a grassy area with enough cover to provide a shady nap. In more populated areas, bears may reverse their sleeping patterns, and their daybeds are typically farther from feeding areas and people. If and when they do hibernate, bears typically prefer areas higher in the mountains, where snow will cover them and their dens. Most dens are located in mountainous and timbered regions.

Diet and feeding habits.

In order to understand how important food is to bears, try raising, or being, a healthy young man. When I was in my teens and early 20’s, large pizzas, entire boxes of cereal, and whole pies were devoured at a single sitting, much to the disbelief of other family members. Now in my 40s, my metabolism is a fraction of what it used to be, and I now stand in awe at the near-insatiable appetites of young men.

A grizzly bear’s appetite is like that of a young man’s. Well, okay, make that about 13 young men! A typical teenage boy requires around 3,000 calories per day, where a grizzly bear preparing for hibernation consumes about 40,000 calories per day! During peak feeding, a grizzly can put on as much as 5 lbs (2.3 kg) of weight a day, building a fat layer 10 inches thick! Lewis & Clark’s expedition described how they obtained 8 gallons of oil from a bear shot on May 11, 1805. May 11 would be in the early spring, after hibernation. Imagine how much oil that bear would have had if shot in late October!

An adult grizzly bear can easily consume 15-20 sockeye salmon per day. Copyright 2009, David E. Shormann

So how much is 40,000 calories in “bear food” anyways? Well, a few calculations of caloric equivalents reveal that an adult grizzly could consume up to 476 cups of blueberries, 44 cups of pine nuts, or 15 sockeye salmon in a day! I could easily see them eating 15 sockeye salmon in a day, even 20. In his book Grizzly Heart, Charlie Russell described how the cubs he was raising would gorge on pine nuts in the fall. But 476 cups of blueberries? If you don’t think that is possible, keep in mind that bears don’t have much else to do all day besides eat, and may spend over 16 hours a day foraging. And if that still seems farfetched, then consider this description from Theodore Roosevelt’s book, The Wilderness Hunter:

“The true time of plenty for bears is the berry season. Then they feast on huckleberries, blueberries, kinnikinic berries, buffalo berries, wild plums, elderberries, and scores of other fruits. They often smash all the bushes in a berry patch, gathering the fruit with half-luxurious, half-laborious greed, sitting on their haunches, and sweeping the berries into their mouths with dexterous paws. So absorbed do they become in their feasts on the luscious fruit that they grow reckless of their safety, and feed in broad daylight, almost at midday; while in some of the thickets, especially those of the mountain haws, they make such a noise in smashing branches that it is a comparatively easy matter to approach them unheard.”

Crowberries are a favorite fruit of Katmai National Park bears. Copyright 2007, David E. Shormann.

During a Lake Creek Alaska Camp, I watched 3 boys fill 3 quart-sized containers with blueberries in 30 minutes. At that rate, after 16 hours they could have picked (but hopefully not eaten!) 256 cups of blueberries. An adult grizzly, with an appetite of 13 teenage boys, could surely pick berries at rates equal to several boys.

Because of the high energy value of pine nuts, it is no wonder that Russell observed his adopted bears and other cubs adeptly dismantling pine cone after pine cone to get at the nuts. And in Yellowstone National Park, squirrel caches of whitebark pine cones are to a grizzly what striking oil is to a wildcatter. Bears will also consume acorns and other nuts, and Roosevelt observed them digging up camas roots and wild onions. Alaskan and Russian grizzlies have a particular fondness for sedges, a reed-like plant of the genus Carex that grows in marshy areas along coasts and stream banks. Lyngbye’s sedge (Carex lyngbyei Hornem) is the most common sedge of south coastal Alaska’s salt marshes and shorelines. It is an important springtime food, with young shoots containing up to 25% protein.

A grizzly cub with a mouthful of nutritious sedges. Copyright 2007, David E. Shormann

Plants make up 60 to 90% of a grizzly’s diet. This may surprise you, since grizzlies are known as fearsome killers! They will also search endlessly for grubs and other small animals, turning over rocks and tearing apart fallen logs. Roosevelt described this behavior in The Wilderness Hunter:

“The sign of a bear’s work is, of course, evident to the most unpractised eye; and in no way can one get a better idea of the brute’s power than by watching it busily working for its breakfast, shattering big logs and upsetting boulders by sheer strength. There is always a touch of the comic, as well as a touch of the strong and terrible, in a bear’s looks and actions. It will tug and pull, now with one paw, now with two, now on all fours, now on its hind legs, in the effort to turn over a large log or stone; and when it succeeds it jumps round to thrust its muzzle into the damp hollow and lap up the affrighted mice or beetles while they are still paralyzed by the sudden exposure.”

Where salmonids are abundant, such as near Pacific coastal areas, and some Yellowstone tributaries, bears will take a break from their herbivorous gorgings to eat their fill of piscivorous snacks. I have observed bears feeding on salmon numerous times in Alaska, and they seem to employ three feeding strategies; stationary feeding posts, snorkeling, and pursuit on foot.

Stationary feeding posts are typically set up in relatively constricted areas of fast-moving water where salmon must funnel through. Prime areas occur at waterfalls or in constrictions in a stream, such as in canyons or newly carved channels. The frothing water hides the bear’s presence, and the salmon, desperate to find the most efficient way to their final destination, either jump over the falls or scurry close to the shore where the current is the least. Like a shrewd businessman seeking to maximize profits and minimize expenditures, the grizzly waits patiently, and captures a meal just by moving his head. Occasionally, fierce fights break out over prime fishing spots, not unlike what happens on some of Alaska’s more human-crowded salmon streams. Popular bear fishing spots are also prime viewing areas for bears, two popular locations being McNeil River Falls and Brooks Falls, where Thomas Mangelsen’s famous photo from the 1980’s was captured.

Bears will also snorkel for food, walking through the shallows with face and eyes completely submerged. I have often wondered how grizzlies, who have color vision of similar strength to ours, can see much underwater. Unless you have some special ability I don’t have, without a mask, everything becomes very blurry underwater to humans. And I don’t think grizzlies have a special translucent nictitating membrane for underwater vision, so they must acquire an ability to discern between blurry salmon and blurry rocks. I have watched a mother grizzly in the lake that Wolverine Creek empties into, and she would snorkel, dive, and capture salmon using her teeth and front paws.

The third salmon-feeding strategy bears employ, and my personal favorite, is pursuit on foot. When salmon are abundant and in about 2 feet (60 cm) of water or less, bears will run through at full speed, leaping and pinning salmon to the bottom. They will also spot a school from shore, and come running along the shore at full speed, making a diving leap off the edge and into the middle of a school. Sometimes they will herd salmon into shallower water for an easier catch. When searching for salmon on foot, bears are intently focused on their quarry, and any smell, sight, or sound indicating a salmon will bring them running. This is an important consideration as you continue your quest to “think like a bear”, because a jumping fish on the end of a line, or even a lazily tossed rock that ends its flight with a loud “kersplash!” can bring a grizzly bear your way in a hurry. When the bear hears that splash, all he is thinking is “food?!”, and he may come quickly to investigate, until curiosity is satisfied.

Grizzlies will also prey upon larger animals, such as caribou, elk, moose, buffalo, and even other grizzlies. Predation of this type is more typical of “interior” grizzlies that may not have the same access to salmon streams as coastal bears. The interior grizzly’s propensity to hunt larger animals also makes it a greater threat to humans, as a bear with experience capturing 200-lb moose calves will have a much less difficult time thinking of ways to hunt down a human. This is why Alaskan grizzly expert Stephen Stringham suggests a minimum distance of 100 yards for viewing unfamiliar coastal grizzlies, and 300 yards for interior grizzlies.

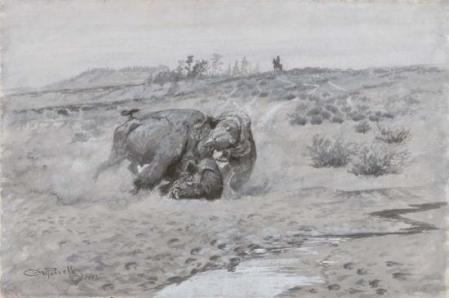

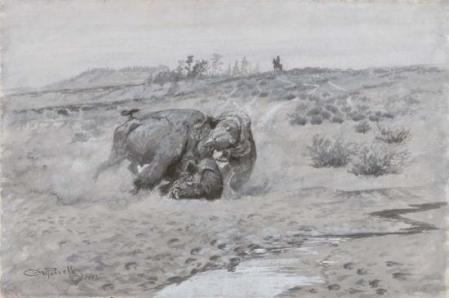

Death Battle of a Buffalo and Grizzly Bear, 1902, by Charles M. Russell. Photo credit: Amon G. Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas.

Bears that hunt larger animals are usually ambush predators. In The Wilderness Hunter, Roosevelt described bears that would hide in thick brush along game trails, while others would stalk the buffalo of the open plains, even pursuing and killing buffalo bulls much larger than themselves. More often though, grizzlies pursue animals that stray from the herd, such as yearlings and calves. In Grizzly Almanac, Robert Busch described a research project by Donald Young and Thomas McCabe, where they found that “grizzlies preying on the caribou herd were found to kill few caribou calves older than 2 weeks of age”.

Roosevelt described grizzlies as animals of “vast strength and determined temper.”, and these characteristics are readily observed in the grizzly’s pursuit of Alaskan moose. In Wild Men, Wild Alaska, hunting guide Rocky Mcelveen described the grizzly’s determined temper as he and some clients observed a grizzly that chased a moose calf and its mother over a mountain ridge and across a large lake before finally capturing and killing the exhausted calf on the shore. Bears (and wolves) are wreaking havoc on Alaskan moose populations, as surveys in Alaska’s Game Management Unit 16B show a 10% survival rate for moose calves.

For grizzlies in the lower 48 states, besides bison, elk are also a favorite food item. In Grizzly Almanac, Robert Busch described a rather gruesome encounter with an elk that showed the grizzly’s “vast strength”:

“Another grizzly’s kill was once witnessed by a Yellowstone park ranger. The bear had surprised a herd of elk crossing the Madison River and killed one of the cows with a single mighty blow to its head with a front paw. The adult elk was killed instantly, the ranger said, in ‘an explosion of brains, blood, and bone fragments.”

Showing their propensity for variety, bears will also capture other live prey, including marmots, prairie dogs, and for coastal grizzlies, delicious razor clams. However, as Roosevelt correctly described them in The Wilderness Hunter,

“the grisly is only occasionally, not normally, a formidable predatory beast, a killer of cattle and large game. Although capable of far swifter movement than is promised by his frame of seemingly clumsy strength, and in spite of his power of charging with astonishing suddenness and speed, he yet lacks altogether the supple agility of such finished destroyers as the cougar and the wolf; and for the absence of this agility no amount of mere huge muscle can atone. He is more apt to feast on animals which have met their death by accident, or which have been killed by other beasts or by man, than to do his own killing.”

Grizzly bears, always looking to maximize weight gain with minimum energy expenditure, are quick to seek out carrion. This is why many a hunter has killed his first grizzly after killing his first elk, caribou or moose, because the grizzly was attracted to the carcass. Grizzlies will often “cache” a dead animal, half-burying it with dirt, grass, or leaves. They will often stay near, and sometimes even lay on top of, the cache, and will defend it vigorously. So here is a word to the wise, if you want to think like a grizzly, have your senses primed for the sights and smells of a cache. If you smell rotting flesh, then it is definitely time to either get out of there, or load the gun/ready the pepper spray, because a grizzly could be very near! Smell will probably be your first clue of a cache nearby, followed by the sight of recently disturbed earth, and finally by the sound of a roaring grizzly telling you to get away from its prize!

Bears will eat any dead animal, including humans. In Grizzly Almanac, Busch describes 5 grizzlies that feasted on a beached whale carcass in Alaska. Charlie Russell also witnessed the same thing in Russia, as multiple grizzlies feasted on the carcass of a blue whale that had washed up on the Kamchatka Coast.

Unfortunately, grizzlies will also feed on the leftovers of humans, becoming experts at raiding garbage cans and garbage dumps. Grizzlies that feed at garbage dumps tend to grow faster and have larger litters, and also lose their fear of humans. At Yellowstone, the dumps were actually a popular tourist attraction, and by the 1930s, at least 260 bears used the dumps. The dumps were shut down in 1971, and today, all garbage is hauled out of the park. Problems still exist in the Yellowstone area though, as a supposedly food-conditioned bear attacked a man in his tent July 18, 2008 at a campsite a few miles from Yellowstone.

Behavior

Parental care is provided exclusively by the mother. Occasionally a mother will adopt cubs. Females interact extensively with their cubs, providing, food, protection, and instruction. Females with cubs tend to avoid males, as males will cannibalize the young bears. More social than polar and black bears, grizzly bear females and older cubs sometimes bond and travel, feed, and defend themselves as a cohesive unit. Weaned individuals often band together with littermates or their non-related peers. Typically, members of bonded groups attain a higher status in social hierarchies, having an advantage at food sources and in defense against larger bears.

Mothers with cubs will often attack and even kill a perceived threat. Adult males will fight each other for territory or mates, but most of the time, bears understand their comrade’s strength, and would rather settle things amicably. In Grizzly Almanac, Robert Busch describes a 1970s McNeil River study by Allan Egbert and Michael Luque, where they found that only 124 of 4,000 bear interactions resulted in striking or biting.

Subadult bears, often referred to as “teenager” bears, tend to cause the most trouble. With the naivety and overconfidence of some human teens, subadult bears venture off into unfamiliar lands, only to be chased off by larger bears, especially males. Teens also get shot at by hunters or landowners, or killed by any of the above. Teens in a group are more likely to raid an unattended campsite than older, wiser bears, and an electric fence or a treed cache is a must when leaving a campsite unattended in bear country.

Bears communicate using sight, smell, and sound, relying most heavily on their keen sense of smell. Feces may contain traces of hormones called pheromones, indicating the breeding state of the animal. In a quiet forest, bears can hear humans talking up to ¼ mile away, and a shy bear may be long gone before you see it. Scratches on trees serve as visual cues to other bears, and the bear’s odor is also left as a mark of its presence. Grizzlies also use visual cues, and if a bear stares at you with flattened ears and a low stance, don’t mimic him! A bear that turns its head sideways is indicating submission, which is a good strategy for people to employ when a bear is showing signs of aggression. Grizzlies communicate vocally as well, using woofs, whines, hums, growls, roars, and “jaw popping”. If you hear a bear pop its jaws, then that means you have a very agitated bear on your hands, and you should start thinking of defending yourself. Charlie Russell observed jaw popping as his adopted young bears played together, but larger bears normally only jaw pop when they are stressed.

As far as animals go, grizzlies are quite intelligent, and are capable of solving a variety of problems in their never-ending quest for food. A bear’s ability to memorize and learn is evidenced by the variety of foods they manage to collect, along with their ability to travel many miles, even returning annual to favorite feeding grounds. Animal trainer Doug Seus trains black bears, grizzlies, wolves and cougars, and of the four, claims that grizzlies are the hardest to tame, but the easiest to train, being able to learn from a single experience.

Conclusions

Now that you have finished a detailed discourse on the grizzly, hopefully you will know how to better think like a grizzly. If you were a grizzly just popping your head out from your winter den, you would be extremely well rested, but also hungrier than you can remember. At this time, you would be likely to eat anything resembling food. As you progressed into mating season, you may be rather annoyed by the presence of other bears, particularly so if you are a male. Moving into summer, food supplies become more abundant, and you relax, even blocking out the world around you as you dreamily feast on salmon and berries. But then, the days quickly get shorter, and without your approval, your body begins craving more food than ever. As you fatten up for Winter, your insatiable hunger reminds you how you felt when you first left your den in Spring, hungry and willing to eat anything that looked like food.

These are the thoughts of a typical adult bear. However, as you will discover in Chapter 7, a female with cubs is a whole different animal!