Chapter 2: The Great Land

Adventure: an undertaking involving danger and unknown risks

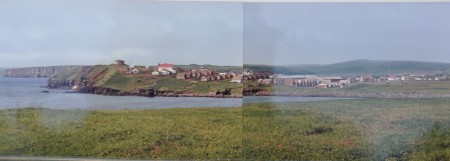

Pribilof Islands

There is probably no better place in the world to have an outdoors adventure than Alaska. The Aleut Indians gave it the name “Alyeska” meaning “Great Land”, which indeed it is. With an area almost 2-and-a-half times larger than America’s 2nd largest state, Texas, and a human population only 3% of Texas’, there is plenty of room to roam. In Texas, we have a saying that “if you don’t like the weather, wait 5 minutes”. This is even more true in Alaska, as I have never seen a place with such rapidly changing weather. And I don’t think I have been anywhere with more rapidly changing weather than the first Alaskan place I visited, the Pribilof Islands.

The Pribilof Islands are composed of two inhabited islands, St. Paul and St. George, and several smaller islands. A common saying on the islands is “”This is the only place in the world where you can experience all four seasons in one hour.” I arrived on St. Paul Island in July 1992 as part of a scientific team studying the local ecology. I was a graduate student at the time, working on my master’s degree in marine science. My advisor, Dr. Terry Whitledge, had worked extensively in the Bering Sea and knew the area well. Whether researching Texas bays, the Mississippi River Plume, or the Bering Sea, his ability to organize and head up an expedition never ceased to amaze me, and this was no different. At a time when the economy of the former Soviet Union was collapsing, Dr. Whitledge had organized this research project, consisting of the two of us and 5 excellent Russian scientists who probably desperately needed some cash.

The Naturalists

While the Russian scientists did not have access to the same array of high-tech tools we had, they made up for that with their knowledge of plants and animals in the area. The Russians were my first experience with people that I would truly call “naturalists”. Up until my master’s degree, all of my education and employment was engineering-related. I started working at General Dynamics in 1989 on the then-secret Navy A-12 project, but the project was canceled in 1990, and everyone was sent back to the main office to work on the F-16 Falcon. I could see the writing on the wall, and after lots of thought and prayer, decided to pursue a master’s degree in Marine Science. The University of Texas’ Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas was searching for graduate students, and I wrote them a rather silly letter about how I wanted to be a “fish conservationist”. Dr. Whitledge liked my engineering background, and while I never directly studied fishes, I couldn’t have asked for a better advisor or a better area of study (water quality). Providence led me down the best path, and I started in August of 1990. That December, General Dynamics released everyone with 5 years experience or less (which would have included me), and I was sad for many of my friends who lost their jobs.

When I started my master’s degree, I had little experience with biology or even science. Engineering is more deductive, where you apply rules in new situations to build things. Science is more inductive, and is about finding rules. And my master’s research focused mainly on water chemistry and a single algal species responsible for creating a “brown tide” in local estuaries.

A love of the outdoors and fishing led me to naturally learn the names of many of the birds and fishes of the Texas coast, but until I met the Russian scientists, I had never met people who were so incredibly gifted and knowledgeable about everything in the ecosystem they were studying. They knew more than just the fish and birds; they could identify practically anything, from the largest whale to the smallest plankton. They loved the ecosystems they studied.

In the book of Genesis, one of the first things God tells Adam to do is name the animals (Genesis 2:19-20). I think one reason God did this was to help Adam care for the animals. One of the very basic ways we care for other human beings is by knowing their names. It is rude and inconsiderate to call out “hey mister” to a person we have known for a while. Not only that, it shows ignorance and a lack of concern. In the same way, if we do not know the names of any of the creatures God has made, it is easier to not care about them.

The Russian scientists taught me a great lesson in the importance of being a naturalist, and this is something I encourage everyone to do, especially children.I think that training children to be naturalists is an extremely important part of their education. In government schools, evolution is emphasized in high school biology, and too much time is wasted teaching this ridiculous theory. Rather than lowering a teenager’s already fragile self-esteem by telling them they evolved from monkeys and that they are products of random chance, it would be far better to teach them about the local flora and fauna and their responsibility to care for it. Students that are more familiar with their local environment are more likely to care about it. But until government schools in America, Russia, and elsewhere start teaching children they were created in God’s image and have a unique purpose, children are much better off learning at private Christian schools or in home schools.

Pribilof Adventures

I had many adventures on that first trip to Alaska. The flight from Anchorage to St. Paul was an adventure in itself. Climbing aboard a Reeve-Aleutian Airlines Lockheed Electra, I noticed the date of manufacture stamped on a bulkhead. I do not remember the exact date, but I do remember that it was before my birth year (1965). I was used to flying in large passenger jets, and getting into this 4-engine turboprop that was older than me was a bit unsettling, but it performed flawlessly, and a few hours later the pilot made a nice landing on the dirt runway in St. Paul.

The next big adventure was driving with one of the Russian scientists, Yuri, from the airport to the house we had rented, which doubled as our research station. Come to think of it, driving anywhere with Yuri was a bit of an adventure. Yuri was in his late 40’s, but had never driven a car. However, he was fascinated with the 13-passenger van we had rented, and he insisted on driving it everywhere. He actually drove pretty well, but his main problem was that he overcorrected, a typical characteristic of inexperienced drivers, and this always kept us hanging on to the seats a little tighter than normal.

Conducting research in the Bering Sea around the Pribilof Islands was amazing. We hired a local captain, an Aleut Indian with a Russian name, Timon Lestenkof. The uninhabited Pribilof Islands were discovered in 1788 by the Russian explorer Gavriil Pribylov. Soon after, Russians forced Aleuts Indians from the Aleutian chain (several hundred miles south of the Pribilofs) to hunt seal for them on the Pribilof Islands.Today, the Pribilof Islands are home to the largest Aleut Indian community in America, and many of them make a good living through fishing. Timon was a wonderful man who had served America in Vietnam. He would take us just about anywhere we wanted to go, provided it was close enough for him to pick up the island on radar, a distance of about 10 miles. This was in the days before GPS was in widespread use, which would have made navigating around the island and beyond much easier.

We would collect water samples from various depths using “Niskin bottles”, and use the winch to raise and lower them. We would also tow plankton nets and store the samples. Northern fur seals would come and visit us while we conducted research, as would fulmars, gulls and kittiwakes. While waiting for us to collect water samples, Timon would sometimes fish. One time I watched in amazement as he tore a 3-inch chunk from an orange-colored rubber glove, threaded it on a hook, and proceeded to catch several 15 to 30 lb halibut. Timon had a painting in the wheelhouse depicting Christ standing behind a sailor, directing Him through a storm. On more than one occasion, the fog set in while we were at sea, and we had to rely on instruments to direct us back to the harbor. The Russian Orthodox church was the lone church on St. Paul, and while I don’t agree with some of their teachings, I am still glad they trust Christ for their salvation. And I was glad that Timon trusted God that our instruments were right and wouldn’t send us crashing into a cliff or a shoal in the foggy weather, which they never did.

One of my favorite parts of research on the Pribilofs was catching seabirds for Dr. Sasha Golovkin. My main job was to perform chemical tests on the water samples we collected, but due to the extreme weather conditions, we often had to wait for days before we could get out to sea. So when I could, I helped the other scientists with their research. I would travel with Dr. Golovkin to the cliffs where millions of seabirds nested, and we would catch and weigh puffins, murres, auklets, anything we could catch. Dr. Golovkin was particularly interested in least auklets, which the locals called “chuchkis”. Dr. Golovkin was studying their diet and metabolism. About the size of a sparrow, chuchkis would fly out to sea in large flocks to catch small crustaceans called copepods. The chuchkis lived along rocky shorelines, and built their nests in the crevices of rocks. In the evening, the chuchkis would return to the rocks, and we would hide behind large boulders, and when a group of chuchkis would come by we would swing large nets into the sky and capture them. Most of the birds were released immediately, but some were kept for further observations. Dr. Golovkin would sample their stomach contents, and they would invariably be full of one species of copepod about the size of a rice grain. Like freshly cooked crabs or shrimp, the copepods also changed from their natural opaque coloration to a pinkish-red color, the heat from the chuchki’s body in essence “cooking” the copepods.

Chuchkis, like puffins and other auklets, were able to “fly” underwater. Denser than most birds, the majority of the chuchki’s body was submerged underwater when swimming on the surface. Dr. Golovkin built a 5-foot square holding tank to observe the chuchkis swimming, and we were all amazed at the ease with which this tiny bird moved underwater. It had to be incredibly agile to catch the small copepods that were its primary food.

We spent many hours exploring the island. There was a 500-head herd of caribou, and one time I spooked them and sent the whole herd stampeding in front of me, inches from the front of the ATV I was driving. We saw many ships hopelessly wrecked on the beaches, along with whale carcasses. Snowy owls, arctic foxes, and of course, Northern Fur Seals inhabited the island as well. The Pribilof Islands are the summer calving grounds for approximately 500,000 fur seals. Almost every beach had fur seals on it, some more than others. In prime spots, there were tens of thousands of seals. The males would form a “harem”, consisting of 1 male and a group of females and their pups. At the larger rookeries, the sound, and the smell were incredible. I could sit and watch the seal pups for hours, playing and interacting with one another. With such an unbelievable amount of animal and bird life, the Pribilof Islands were one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever visited, and highly recommended, if you can stand the smell.

Dr. Flint photographing a baby Arctic Fox. Note the caribou herd in the background. Pribilof Islands.

Mainland Alaska-Kenai Peninsula

Research continued on the Pribilof Islands in the summer of 1993, and I was also able to experience a bit of the mainland and its world famous salmon fishing opportunities. Before I left for the Pribilofs that summer, my father and I .made a fishing trip to the Kenai Peninsula. Our destination was the Kenai River and a guided trip for king salmon. While the majority of Alaska is devoid of people, the Kenai River in late July is not one of those places. Known worldwide for the incredible size of its king salmon, the Kenai River is probably the busiest river in Alaska. If you are looking for pristine wilderness, the Kenai River is not the place to be, but if that doesn’t bother you, then it is a beautiful place with lots of fishermen.

We failed to catch a king salmon on our trip, although one of the men in our boat did land a beautiful 50 pounder. The Kenai River also sports one of the largest sockeye salmon runs in the state, and anglers flock to its banks for this tasty prize. Since sockeye are very reluctant to strike a lure, fishermen must basically “snag” the salmon in the mouth with a streamer fly. Occasionally they do strike a lure or fly, but most sockeye are caught by snagging them in the mouth. I managed to hook a few, but my tackle, which was meant for light-tackle speckled trout and redfish in Texas bays, was no match for the combination of powerful fish and strong current.

Those two summers on the Pribilof Islands, and the time spent reading about Alaska, had me hooked for life, and I was determined to make it back to this great land. Besides the wildlife, there were other features about Alaska that intrigued me as well, such as the mountains, volcanoes, and glaciers. Alaska seemed to have everything an outdoors enthusiast could want, and in 2000, I was able to return again with my father.

As a young boy, my father would take me fishing, and before long, I was passionate about it. Growing up in Kingwood, Texas, I would ride my bicycle several miles to the San Jacinto River and fish for catfish and bass. My love of fishing seemed limitless, and I pestered my hard-working father to no end, constantly wanting him to take me fishing. I am now more reasonable about the amount of time and effort I put into fishing, but I still love to go, and my second fishing trip to Alaska in 2000 is one I will never forget.

West Cook Inlet

On this trip we decided to head to the west side of Cook Inlet to fish for silver salmon. It was early August, and the silvers were beginning to show. We were on a guided trip with Talon Air Service, and took a float plane to fish the Kustatan River. The river was high and muddy from recent rains, and the fishing was slow. Growing up fishing the spring run of white bass on the Trinity River, I knew that the bass would stack up in clear sloughs and creeks when the Trinity ran high. I had noticed that we traveled down a clear slough to get to the Kustatan, and suggested this as a possibility. We returned to the slough, and immediately began catching silvers almost as fast as we could get a line in the water. We had our limits in short order.

The next day we had a halibut trip scheduled, but it was canceled due to rough weather. We decided to try again for silvers, but this time we fished a spot where Wolverine Creek emptied into Big River Lakes. We had great success with silvers again, but more than that, we were treated to front row seats of a mother grizzly bear catching salmon for her two cubs. This was the 2nd wild grizzly bear I had ever seen, and my first Alaskan grizzly. Little did I know that it would not be my last. Sockeye salmon were stacked up beneath the outfall of Wolverine Creek, and the mother grizzly had easy pickings. When a large male black bear came on the scene, the mother grizzly bear chased him up a steep incline. We simply could not believe how an animal of that size could move so quickly up something so steep.

Wolverine Creek was a fascinating place, and after we had caught our limit of salmon, I persuaded the guide to let me out of the boat to get some pictures of salmon swimming up the creek. Several people cautioned me about the mother grizzly being nearby, but I could not see it and proceeded upstream. There were at least a dozen boats fishing in the area, and the mother grizzly seemed perfectly at ease, so I was not too apprehensive about hiking up the creek.

Suddenly, someone spotted the mother grizzly bear heading towards the creek, and everyone started yelling at me to come back to the boat, but I could not hear them because of the rushing water. It was not until I saw my guide approaching and waving his hands that I realized I needed to get back. The bear kept approaching, but it never charged or seemed concerned about my presence on the creek. This was my first experience that convinced me of the fact that all wild grizzlies are not ferocious man-eaters.

I took more photographs of the mother grizzly bear and her cubs than of anything else that trip. As I photographed the bear, I couldn’t help but think about Thomas Mangelsen’s photo I had seen back in 1989. That photograph was such a perfect trinity of bear, salmon, and photographer. It revealed the incredible abilities of all three, the bear and its hunting prowess, the salmon and its ability to leap up and over a rushing waterfall, and the photographer’s ability to have the camera settings optimized for the occasion. The bear I was photographing had a different hunting technique than the Mangelsen bear, and would “snorkel” and then dive down about 6 to 8 feet to catch its prey. And while I knew I would not get any photos like the Mangelsen bear photo, that snorkeling bear provided plenty of opportunities for photography practice, and made me realize more than ever that I wanted to be around these magnificient creatures and the salmon streams they loved.

After returning home from the 2000 Alaska trip with my father, I spent hours looking over the photos I had taken, longing to return to Alaska. Flying on the float plane, as well as observing the huge number of aircraft flying in and out of the Lake Hood float plane airport in Anchorage, made me realize that to get “off the beaten path” in Alaska, I would need to either go by plane or by boat. Since 1997, I had been conducting Marine Science Camps in Port Aransas, and the thought occurred to me that I should attempt an Alaska Science Camp. I discussed the plan with Rob Sadowski, a former student-turned-camp-assistant, and he couldn’t agree more.

By the summer of 2001, my beautiful wife Karen, and I owned two math and science education businesses, we were homeschooling my 15 year-old son, Kenny, and we were the proud parents of a daughter born in June. When Christ said He came to give us an abundant life, He wasn’t kidding, and mine was getting more abundant by the minute. I knew though that for some reason exploring Alaska figured into the picture of this abundant life, and I was determined to find out how.

Explore posts in the same categories: Grizzly Adventure, a book in progressTags: Arctic Fox, Black-legged Kittiwake, Crested Auklet, grizzly bear, Horned Puffin, Kustatan River, Northern Fur Seal, Pribilof Islands, Russian scientist, Sockeye Salmon, St. Paul Island, Stellar's Sea Lion, Wolverine Creek

Both comments and pings are currently closed.